Why Word Choice Now Matters in the Maduro Story

A small stack of words can change how we see a historic moment. So when the **BBC reportedly told its journalists to avoid calling the United States’ removal of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro a “kidnapping,” the reaction was swift and intense online.

This isn’t just newsroom housekeeping, it’s a reminder that language isn’t neutral.

What the BBC Memo Says and What It Doesn’t

According to British media commentator Owen Jones, an internal BBC editorial memo instructed staff not to use the word “kidnapped” when reporting on the dramatic US operation in Caracas that removed Maduro from power. Instead, journalists were to use terms like “captured” (when attributed to the US government’s description) or “seized” when describing the event themselves.

The memo was reportedly discussed at a 9am editorial meeting — dubbed “the Nine” internally — to promote “clarity and consistency.” But critics say that instruction risks framing the action in softer diplomatic language, rather than accurately reflecting the force used.

BBC journalists have been banned from describing the kidnapped Venezuelan leader as having been kidnapped.

The BBC News Editor has sent this to BBC journalists. pic.twitter.com/jn9qQZkVAH

— Owen Jones (@owenjonesjourno) January 5, 2026

A Global Raid, a Global Debate

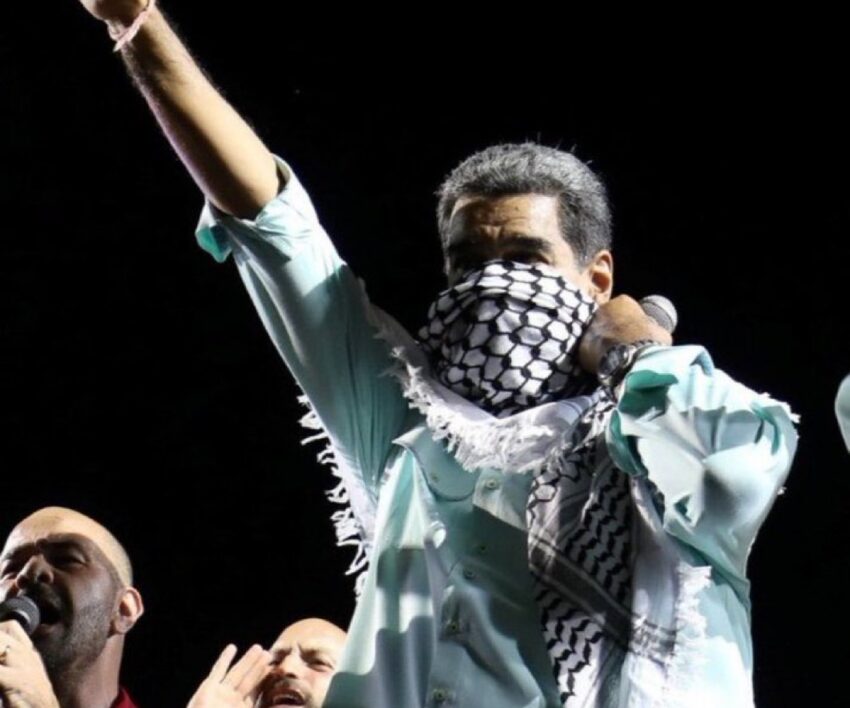

Maduro’s removal gripped headlines worldwide: a US special‑forces raid in Caracas ended with him and his wife flown to New York to face drug trafficking and weapons charges, charges he vehemently denied in court, insisting he was “kidnapped.”

This legal drama alone — a foreign leader on US soil facing prosecution — was already extraordinary. But the choice of words used to describe it has turned into a story itself.

On social media and news forums, journalists, media critics, and everyday internet users have taken sides:

-

Some argue BBC guidance amounts to sanitising the story to align with Western power structures.

-

Others note that “kidnapping” is a legally loaded word, and a major international broadcaster might reasonably avoid it unless a court has ruled the act criminal.

-

Many commentators pointed out the difference between reporting what Maduro said and making editorial judgments.

Why This Matters to South African and Global Audiences

For many South African readers, the BBC still carries weight as a global news authority — especially for foreign affairs. But decades of media debates over language, bias, and framing have made audiences more media‑savvy. Words like ‘captured’ and ‘kidnapped’ aren’t just semantics: they shape how we understand sovereignty, legality, and fairness.

South Africans — whose own media landscape has grappled with questions of state influence, impartial reporting, and historical framing — may find this particular debate familiar. It raises two big questions: Who decides how we report powerful nations’ actions? And should media neutrality sometimes give way to naming facts as they occurred?

Government and International Reactions Around the World

Even politicians have waded in. In the UK, Prime Minister Keir Starmer avoided saying whether the US action breached international law, emphasising Britain’s support for a peaceful democratic transition instead.

Across Latin America, many leaders condemned the US military action as a violation of sovereignty — arguing that removing a sitting president by force looks very much like an abduction under international law.

BBC’s Track Record Under Scrutiny

This isn’t the first time the BBC has found itself at the centre of editorial controversy. In late 2025, the broadcaster apologised for altering a speech by ex‑US President Donald Trump in a way that implied he encouraged violence on January 6, 2021 — a mistake that triggered internal resignations and a $10 billion defamation suit.

Critics of the recent guidance say that if editorial policy can shift how a major incident like the US’s seizing of Maduro is discussed, it undermines public trust, particularly at a time when global tensions are high.

How Journalists and Viewers Are Reacting Online

On platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and Reddit, discussions range from media‑theory dissections to sharp critiques of the BBC’s choices. Some users argue the policy is simply responsible journalism, avoiding a term that implies illegality before a court decision.

Others see it as part of broader concerns about how Western media describes international military actions, a debate with real impact on public understanding.

Words Matter and So Do Audiences

At a time when global politics are intensely polarized, the BBC’s memo has done more than guide internal newsroom language, it’s launched a wider discussion about how news outlets balance legal precision, neutrality, and truth‑telling.

For readers far from Caracas, from Cape Town to the Caribbean, this episode is a reminder: how the story is told matters as much as the story itself. And in a connected world, every editorial decision sends a message.

Source: IOL

Featured Image: X{@ShaykhSulaiman}