When South African influencers began promoting the Alabuga Start Programme, it seemed like another opportunity in a sea of sponsored posts. But within weeks, the programme was making headlines, not for opportunity, but for allegations that it left young women exposed to human trafficking networks.

The Russian Embassy, responding to the backlash, dismissed the claims as “unfounded allegations,” pointing the finger at “biased outlets” for spreading panic. Still, the controversy has left a bitter aftertaste for local audiences, many of whom feel betrayed by the very influencers they trusted.

Why Influencers Are in the Hot Seat

South Africa’s influencer economy has exploded in recent years, offering young creators a way to monetize their platforms and stand out in a tough job market. But with youth unemployment hovering above 40%, promotions linked to jobs or training programmes hit differently.

For young followers desperate for opportunities, a post by a favourite influencer can feel like a lifeline. That’s exactly why this controversy has cut so deep, it isn’t about discount codes or product endorsements, but about the trust economy that influencers thrive on.

Local Twitter (X) users have been unforgiving:

-

“You can’t play with people’s futures like this.”

-

“Influencers need to know they’re not just selling makeup anymore; they’re selling hope.”

Who’s Supposed to Keep Them in Check?

The Advertising Regulatory Board (ARB) is South Africa’s main watchdog for advertising standards. While brands and agencies are usually members, influencers are expected to follow the rules too, thanks to Appendix K, introduced in 2023.

These guidelines are meant to keep influencer marketing honest: clear disclosures, no hidden ads, no misleading promotions. Hashtags like #ad or #sponsored are non-negotiable. Importantly, accountability is shared, both the influencer and the brand can be held responsible for dodgy promotions.

But here’s the catch: the ARB governs advertising, not recruitment. Programmes like Alabuga Start don’t fit neatly into the usual categories. Was this an ad, a job listing, or something else entirely? That grey area has left a dangerous gap in regulation.

What Happens When They Break the Rules?

The ARB can order takedowns, issue Ad Alerts, or publicly shame influencers who cross the line. While it doesn’t hand out fines, reputational damage can be brutal, losing brand partnerships is often punishment enough.

Still, enforcement is shaky. Some influencers bury disclosures at the end of captions, use vague tags like #collab, or delete posts quietly after backlash. By then, the harm is already done.

The Alabuga scandal isn’t just about one programme, it’s about the blurred line between influence and responsibility. In a country where desperation for work runs high, promoting overseas opportunities without vetting them isn’t just careless, it’s potentially dangerous.

For now, the Russian Embassy insists nothing sinister is happening. But the debate has already shifted closer to home: can South Africa’s influencer culture survive without stronger accountability, and are audiences too quick to trust personalities who may not understand the risks of what they’re selling?

What’s clear is this, when influencers trade on trust, every post becomes more than content. It becomes a contract with their audience. And breaking that contract, especially in a country so vulnerable to false promises of work, may come with consequences bigger than an Ad Alert.

{Source: IOL}

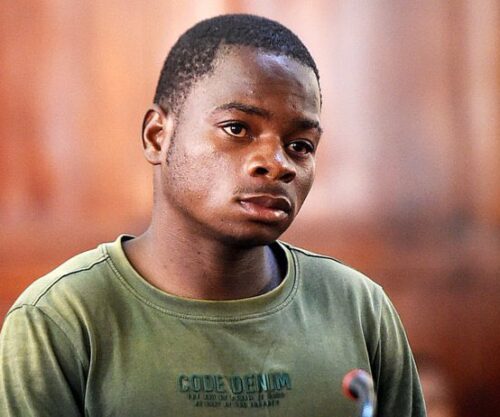

Featured Image: X:{@sezalabuga}